Breathing Gears vs. Heart Rate Zones

Let's clarify terminology and learn how and when to use these metrics and corresponding practices to develop our physiology.

In addition to beginning a capacity training cycle, I’ve also started focusing on breath work — a very complimentary process as I’ll explain in my later review of that training cycle.

In his “The Uneasy Athlete” webinar, Brian Mackenzie mentions that chess players can burn 6,000 calories per day and that free divers can burn 600 calories per hour with a heart rate well below 60 bpm.

Immediately, I was curious; not skeptically dismissive, but intrigued. After some quick Google-ing I found that free divers can drop their heart rate as low as 10 bpm (ref.) and scuba diving burns about 600 calories per hour (ref.).

As for the chess players, an article from ESPN cited that grandmasters can burn 6,000 to 7,000 calories per day (ref.) and that their heart rate elevates from about 75 bpm to 86 bpm (ref.). Interestingly enough, their carbohydrate metabolism decreases and fat oxidation increases.

I familiarized myself with heart rate zones during the endurance program I underwent last summer / fall — typically working in the Zone 2 or “conversational” pace around 60% max heart rate.

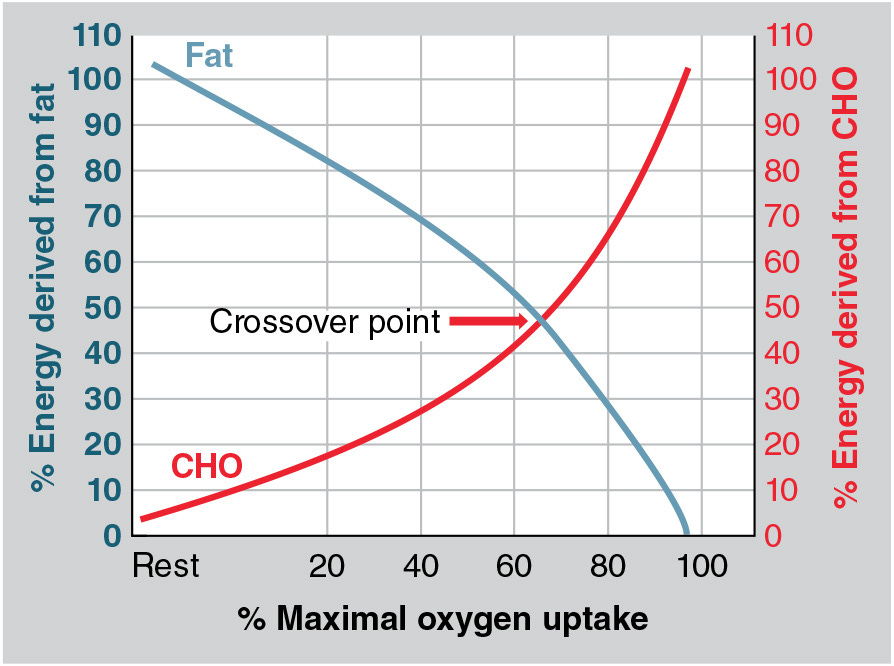

Technically cardiovascular zones are measured in terms of VO2max, though as seen above it’s often much easier to work in terms of percent-of-max-heart-rate. Those aren’t quite the same, but one is a lot easier to monitor and measure; particularly intra-workout.

However, during the program I often measured my “Zone” by monitoring my breath cadence (rather than looking at a heart rate monitor every few seconds).

For me this was:

(nasal in) puff-puff-puff

(mouth out) steady-1-2-3

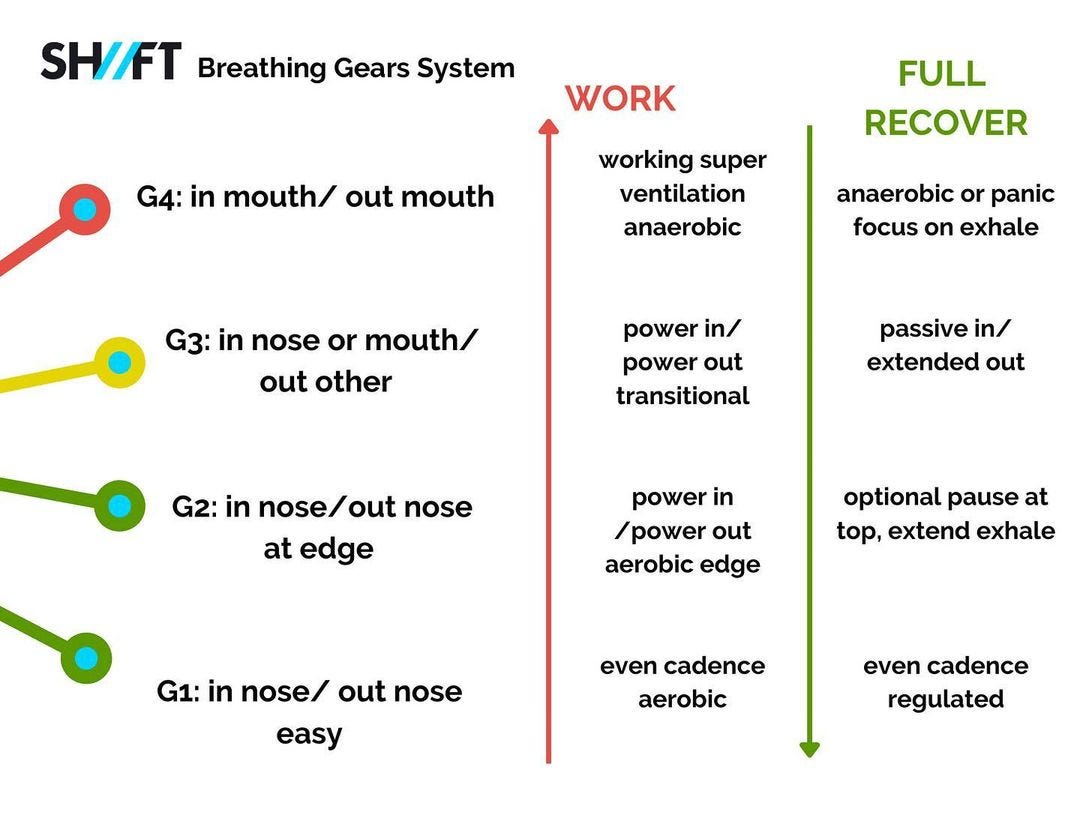

Older documents / videos from Shift Adapt show 5 Gears:

in nose / out nose (even, easy)

in nose / out nose (power in, easy out)

in nose / out nose (power in, power out)

in nose / out mouth

in mouth / out mouth

My “Zone 2” breathing cadence was somewhere around Gear 3 based on the descriptions above. According to the heart rate logs I kept I was pushing a bit past Zone 2 to Zone 3, but you can definitely see overlap in the systems being utilized regardless of the terminology used to describe them.

What we’re essentially trying to describe is:

gas exchange

fuel / substrate consumption

I’ve talked about the crossover effect many times before, but I’ll note again that the above graph is a general approximation. The 60% VO2max “crossover” point can be manipulated by variables such as body fat, fat adaptation, and proficiency with the tested movement (ref., ref.).

I mentioned using heart rate as a representative measure of VO2max, but that is a very rough translation. The reason being is that oxygen utilization (in conjunction with CO2 production) can be used to manipulate energy substrate consumption. This is called respiratory exchange ratio, or respiratory quotient (ref.).

Generally, a RQ of 1.0 is indicative of carbohydrate oxidation, and fat oxidation has a RQ of about 0.7. This is all very interesting when one then asks, why do we mouth breath at all?

Well, we’re built to use multiple energy substrates. However, the vast majority of people in the West have grossly dysfunctional metabolisms (from dietary pathology) which are compounded by bad breathing.

Let me give you a live example:

Strat at an easy pace on a bike erg.

Only breath in / out through your nose.

Add 2 RPM each minute.

Note the RPM and duration when your mouth has to open.

A few things to take away here are that when we breathe through our mouth:

We intake more oxygen (good for performance).

More of what we breathe out is oxygen (bad for performance).

We’re burning mostly carbohydrates.

Now, the problem with this is that it contributes to our perpetual “wired but tired” modernized life. If you’re running from a tiger, you need all the rocket fuel (glycogen / sugar) you’ve got stored and as much oxygen as you can handle regardless of exhaust biproducts (like a car’s turbocharger).

However, if I’m sitting at my desk typing this article, there’s no reason to be that activated / stressed / revved up — hence more metabolic dysfunction is induce by my breathing pattern in addition to whatever poor food choices one may be making.

Conclusion:

This has been an interesting re-frame for me. I’ve grown fond of the expression that:

Breath is clutch.

This is especially relevant during my recent endeavors in capacity training. That is, if one is “passively resting” you may well be hyperventilating and “wasting” the off-period. Bringing attention to, and trying to regulate your breath between (and even during, though this is less voluntary) work intervals can make a huge difference.

However, much like being in a relationship and telling an angry partner to “just calm down”, or downshifting a car too soon, you get a similar effect:

Therefore, it’s important to know how and when to brake (hold) before shifting; both with the car, and with your breath — and your partner too. That is, if your panting from a sprint, trying to immediately nasal breathe will likely induce more panic — as will an extended hold due to CO2 pressure rising.

So, you might consider the following instead:

Activity to induce > uncontrolled mouth in / mouth out

Attempt to pause 1 second (at the top of each inhale), until it’s easy

Mouth in / mouth out, but try to extend the exhale by 1 second, until it’s easy, then add another second to the exhale

Nose in / mouth out (powerful, then steady, until it’s easy)

Nose in / mouth out (hold inhale for 1 second, until it’s easy)

Nose in / mouth out (extend exhale)

Nose in / nose out

#onward #defendanalog