Westside Barbell and CrossFit are two of the most well known, respected, and even controversial names in the fitness industry. Recently WOD Science posted a couple “CrossFit versus…” posts; so let’s take a closer look at what we can learn from this in a sport-specific context.

I want to start by giving credit where it’s due. As usual, Zach Telander has done a great job already covering this topic with his take and I wanted to chime in with my $0.02 as well.

As Zach and many of the comments on the first WOD Science post (1) point out, that particular discussion is really “good CrossFit” vs. “pop cross-fit.” What get's called “traditional crossfit” is really just “doing too much (at once).”

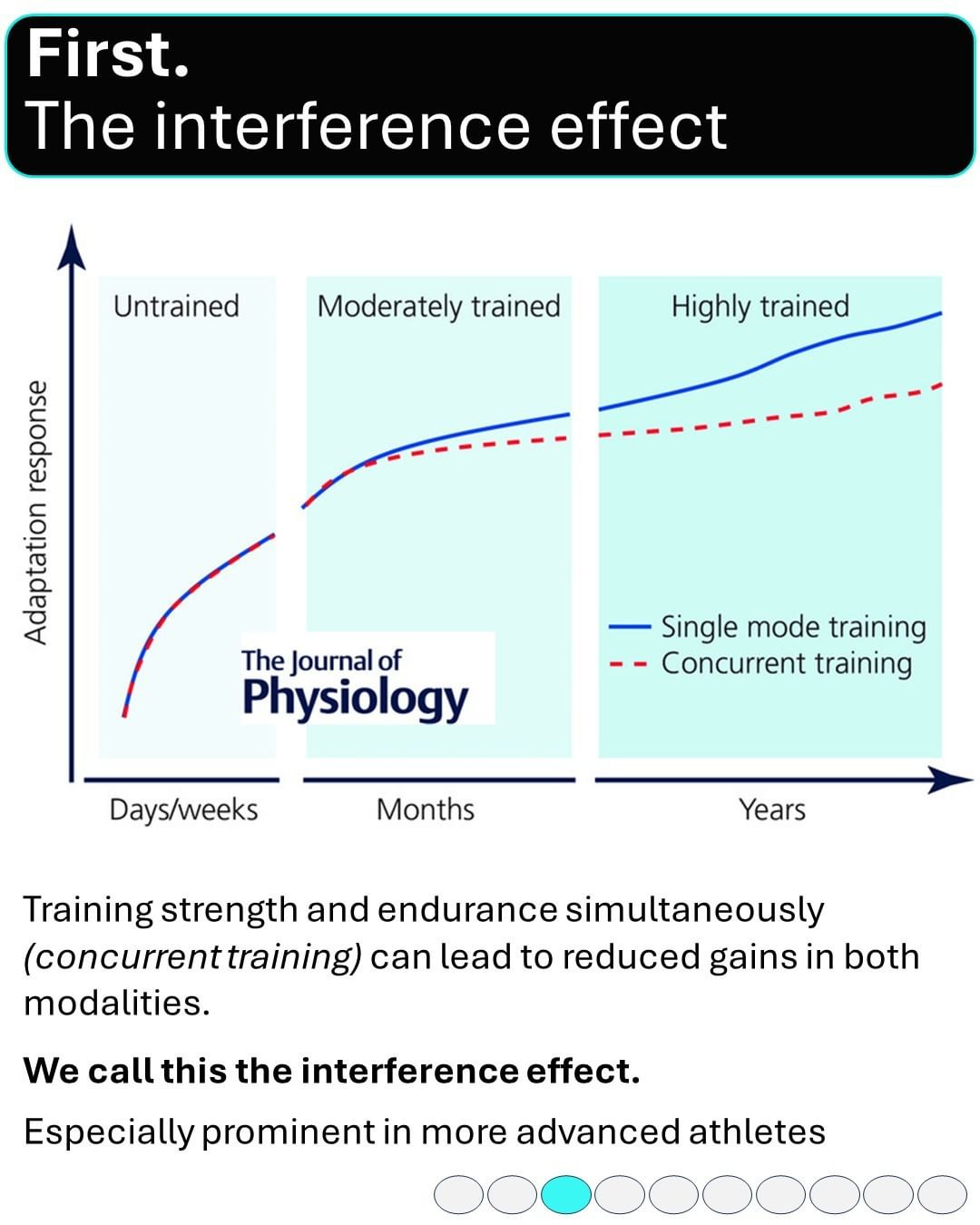

You can get better at most things. You almost certainly can’t get better at everything all at once — unless you’re extremely inexperienced. As Dan John reminds us, “chase two rabbits, go home hungry.”

What this looks like is what you see in a lot of “evidenced based”, “conditioning”, group classes. Again, at a vary basal level, that may be necessary and you may see significant improvement; but there’s a reason rates of burnout are high and delivery of results is subpar.

Sessions like this typically incorporate some kind of general warm up, followed by strength or skill training, followed by metabolic or lactate training. There has been some recent literature that low intensity cardio won’t kill your strength gains, even in the same session; but that’s not what we’re talking about here.

The biggest problem I see with this is that it lacks focus and makes things overly complicated. What we see as effective training for recreational athletes also scales for professionals. Professional fighters, for example, may train multiple energy systems within the same day — and often do.

However, it’s almost never within or in back-to-back session. There’s a delay. For example road work (endurance) in the early morning, technical sport (skill) work in the mid-day or afternoon, and strength training later in the evening.

What is true for the professional on the micro (daily) schedule, is also true for macro-cycles or training blocks. If I’m in a “strength block” I want most of my time to be spent on that. So, even if “the science” says extra endurance work won’t kill my gains, it still takes energy to participate in and to recover from.

We have to accept that excellence implies exclusion, particularly the more advanced or specialized we get in our training. That doesn’t mean I won’t do any endurance work during a strength block, it just means I have to choose what I want to actively develop and what I want to maintain — like the “cooking” vs. “simmer” burners on a stove.

WOD Science made a follow up post (2) which seemed to add to the confusion — and of course everyone has an infallible opinion in the comments. Again, the terminology and parsing of words muddies the waters when in reality it’s not that complicated.

Metabolic conditioning, or capacity training implies a descent down from maximal loads. The optical illusion, the narrative we tell ourselves, is that we will be the exception to not regress towards the mean and that we can forever “sharpen” ourselves.

Somewhere around 70% 1RM you can pack in a lot of volume. You may even be able to torture yourself by shortening rests and increasing session density (work:rest ratio). This is good for a while, but we’d be well served to know that this sharpening eventually makes us brittle.

There’s a limit to how much 70% training will help you adapt to moving that 1RM upwards. Likewise, trying to “strength your way through” a grueling endurance-type session that’s meant for loads < 30% 1RM is going leave you disappointed — but by all means, try it if it’s a lesson you have yet to learn.

Mentioning Westside Barbell (WSBB) in the title wasn’t just click-bait. They’ve figured a lot this stuff out already. While they use different terminology than myself (max effort, repeat effort, dynamic effort); we’re describing similar functions and execution.

Most importantly for our discussion here, we’re talking about cycling our focus on a specific energy system or training style for a given session, week, block, or other time frame.

Louie Simmons himself was critical of the “block periodization” terminology I use (3) though the “wave periodization” principle he talks about is still applied. This is mostly an echo of the fact that most of our lives don’t pan out on a perfectly segmented ritual — as if one can endure “progressive overload” indefinitely anyway.

Going back to the stove metaphor, did you forget to turn on the back burner? While you’re “cooking” the “strength pot”, did you let endurance go cold? Or vice-a-versa?

Bringing this back to grappling then, what matters is results. If I “invent” a new conditioning system called “The Potato System”, and I:

convince a financial backer to give it all kinds of marketing hype, which…

garners dozens of “studies”, and I…

open up hundreds of affiliate gyms across a global scale, the impact of which…

radically revolutionizes the way people conceptualize fitness and their engagement with and of their bodies…

Does it matter if we call it the “poh-tay-toe” or “poh-tah-toe” system? No. What matters is whether or not results are delivered, and if the delivered results are what one was seeking when implementing the system / method.

Long before fitness became a sport of its own, the idea of being “cross fit” was just that. It was a question of how can we go beyond General Physical Preparedness (GPP) in terms of developing “functional fitness” that’s applicable across a vast sporting spectrum?

To “conjugate” means to join or come together. Louie meant this in terms of Russian and Bulgarian strength paradigms. To play even more word games, in mathematics and physics, a conjugate is:

an element of a mathematical group that is equal to a given element of the group multiplied on the right by another element and on the left by the inverse of the latter element (4)

In other words, “there are many paths to the same summit.” Or “how we got there” matters much less than “did we get where we wanted / needed?”

We see a similar “boxed” or “trademarked (TM)” problem in BJJ and in the health / nutrition spaces as well (queue trademarked diets like Whole 30, Dolce, Zone, Atkins, etc.).

Surely, dear reader, you are well informed enough to connect the dots and see the similarities between an approach to fitness that is “conjugating” and / or crossing (between, over, within?) different energy systems and the demands of your given sport.