Limits, Failure, and Breaking the 7-Day Training Cycle

A more intelligent approach to training work capacity?

Failure can teach us a lot of things. I wanted to take another stab at building my work capacity after the last training block fell short. I wanted to return to you with a valiant comeback story. What I was forced to reconcile was that everybody’s body has limitations, including rate of adaptation.

Failure, while educational, “doesn’t always inspire one to continue.”

The point of training though, is always development, education. Rarely does that require one to vomit during a training session, though it will always demand attentiveness to and testing of limits.

One of the things I learned and overlooked was my recovery need. That is, I pre-programmed what I thought would be adequate rest on a weekly schedule for the next several weeks.

This error had a demoralizing effect, but to the point that the prior training was effective, I was able to assess and adapt.

The “Rule” of 10 Sessions:

Out of every 10 training sessions, 6 will be more-or-less average (a little up, a little down), only 1 will be rockstar-great, and three will be so devastating you’ll wonder why you even started this activity.

I don’t remember where I first heart this, and the numbers are somewhat arbitrary, but the ratios work themselves out generally speaking. Another way to envision this concept is with training intensity — how often can I truly give a 100% effort?

1 / 10 training sessions wouldn’t be a bad guess. I’d also wager that for at least 3 sessions (of 6 moderate ones) you try to convince yourself you’re going hard; but what you’re really doing is staying comfortable. I’ve caught myself in this rut many times; which leads to focusing on the 10% that doesn’t matter.

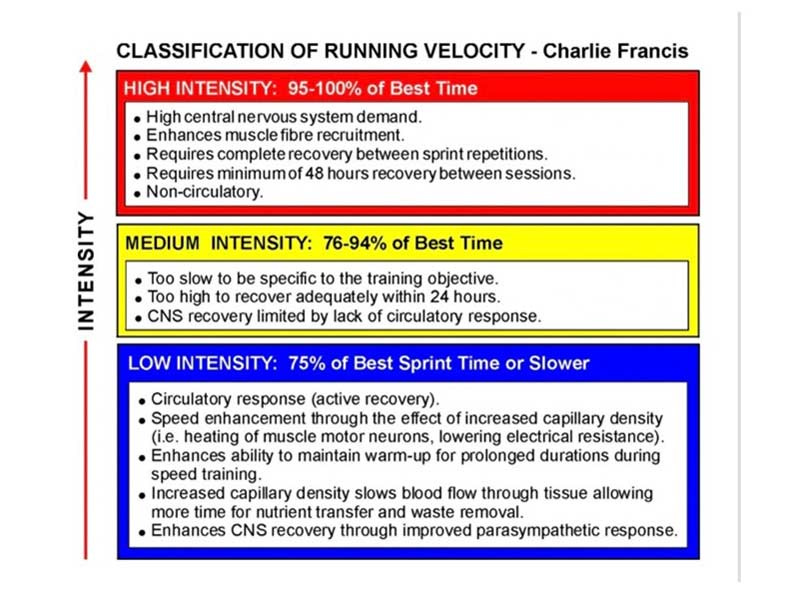

Charlie Francis and the High-Low Model:

Controversy aside, Charlie Francis was one of the greatest track coaches of all time. With or without PEDs his methods are sound and still used around the world in variety of incarnations.

That “medium” intensity is where people get stuck. It feels hard, because it is too intense to recover from quickly, but it isn’t intense enough to force novel adaptation (i.e. training). Hence, this is really avoidance of “detraining” and impairs progress overall.

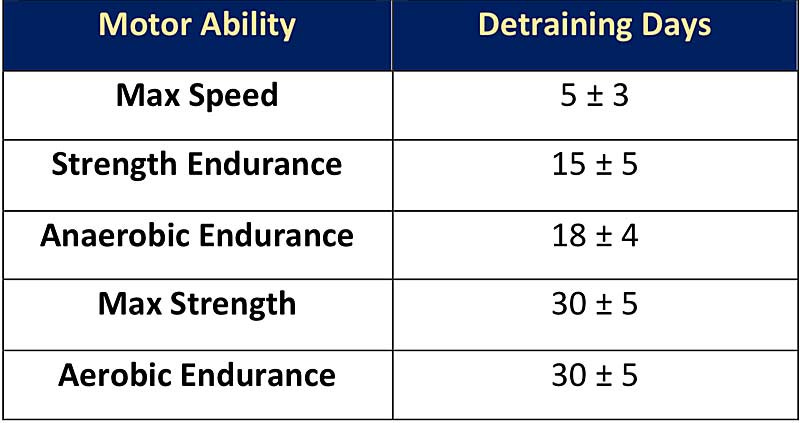

Above is another chart from Charlie that’s helpful for trying to plan long training cycles for an intensity-focused, but well rounded athlete (e.g. sprinters).

Let’s see what we’ve got at face value:

“Max” training 2x / week

e.g. heavy sets, sprints

“Strength Endurance” 2x / month

e.g. Alactic recovery / recoverability intervals

“Anaerobic Endurance” 2x / month

e.g. Lactic threshold / O2 mobilization

“Max” testing 1x / month

e.g. heavy singles or doubles

One “long” run / month

e.g. endurance

I haven’t mapped this on top of other templates, but on the surface it doesn’t look like a bad training plan.

Images from “Charlie Francis Training System”, sourced from simplefaster.com

What’s interesting about that last image (above) is that it immediately makes me think of recovery. Specifically, work:rest ratios. Let’s take an Assault / Echo Bike example. If you did 10 sprint intervals of:

10 seconds,

20 seconds,

30 seconds,

60 seconds,

2 minutes, or

5 minutes,

How long would you need to recover enough between sets to reproduce the results? How does your perception of “effort” and “pace” change if I now tell you that you can only rest for 50% of the time you were “working?”

Generally, work:rest ratios of 1:1 are a good starting point for high intensity training. However, when we drift to 2:1 or more, we subconsciously pace ourselves. In the above examples, very different sensations should come to mind.

If that’s not the case, I suggest you try the examples and observe for yourself on your next training session.

Power Lifting and especially Olympic Lifting are good reminders here. The barbell may only be moving for a few seconds, say 3 - 7, yet rest between heavy sets may be 5 - 10 whole minutes.

Quantifying Recovery Need:

RPE or “rated physical exertion” does not always translate to output or performance.

There are all kinds of charts out there that map this on top of other scales (like VO2max or percent of max heart rate). Your perception, and thereby the scale above, can be easily swayed.

Instead, I’ll suggest thinking in terms of recovery, what a given effort will cost you regardless of “perceived exertion.”

10 - an unreapeatable performance, done infrequently, impossible to repeat in the same day or even week.

7-8 - a good working load, effort is repeatable within the week, but certainly not within the same day and probably not tomorrow.

5-6 - this is a good warm up, sensations of starting to have to “try.”

2-3 - easy recovery sets, could be done for substantial period without stopping.

When estimating recovery need we can ask ourselves, "how far outside my comfort zone did I go?” In terms of load? Volume? Intensity?

Typically the “doubt monsters” start to creep in around 30% - 40% (or the second quarter) of an effort. While, despair usually creeps up around 60% - 70% (of 1RM or through an endurance effort).

This despair, if we push through it, is where we grow, and if we allow ourselves to then recover “training” has successfully occurred. However, if the despair gnashes away at our identity with swayed perception, we resign ourselves and default to “practice” or avoidance of detraining.

Capacity Manual Follow Up:

What I’ve learned is the cost of intensity, and that is recovery. World class intensity requires world class recovery. In other words, I can’t arbitrarily identify that:

“Tuesday will be my hard day.”

What if Saturday’s grappling was unusually hard? What if I missed the Saturday session because of some other life obligation and made up my “hard sport” session on Sunday?

7-day splits are fine if your intent is limited effort (comfort, practice, medium-intensity). However, we must be honest with ourselves. If I am truly pushing myself anywhere near a “limit” — or seeking one out because it has yet to be defined — then I must accept that I will not find the answer until I’ve gone too far.

Conversely, holding something in reserve means potential left unrealized. Honest actions must be taken because their consequences are irrefutable. If I am set on “training intensity”, I must allow that — and all it demands — to be the priority.

Continuing to Address Limitations:

Fortunately, I don’t have to abandon “capacity” work all together. I made an effort to address several limitations in the past year; notably O2 mobilization, and endurance before that. I’ll be honest, in both cases I’ve little desire to do:

300 FY (10 minutes on air bike for max calories), or the

Space Race (6-hour AMRAP, 40 bike calories + 400m run)

Any more frequently than about twice per year each. However, those two set the stage nicely for training “recoverability.” This could be inter-effort (between rounds in the same session) or inter-week (between training sessions).

However, movement deficiencies creep in everywhere. Obviously if you are not efficient at a given lift / exercise / movement, you’re going to use more oxygen, have more substrate build up, and have more difficulty recovering.

With that said, my shoulder mobility has improved a lot this year, but I still have some nagging hips which are largely held back by rigid ankles.

What tackles all of these, looks awesome, requires a high degree of athleticism, explosiveness, and translates very well to grappling?

Olympic lifts my friends! I’ve never been “good” (or even okay) at them, so I’m taking the time to “be a white belt again.” I hope you enjoy watching and reading about the process!

Coming soon…