About this program:

This program is intended to follow a “minimalist” design. If you don’t know where you’re at, this is a great place to start! However, finding out where you’re at is integral to where you’re going and how to get there.

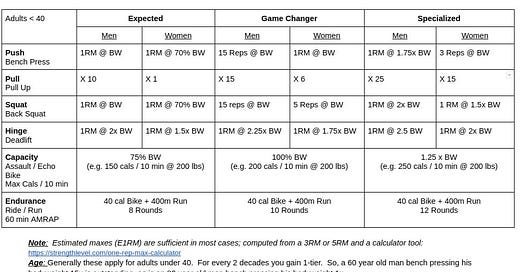

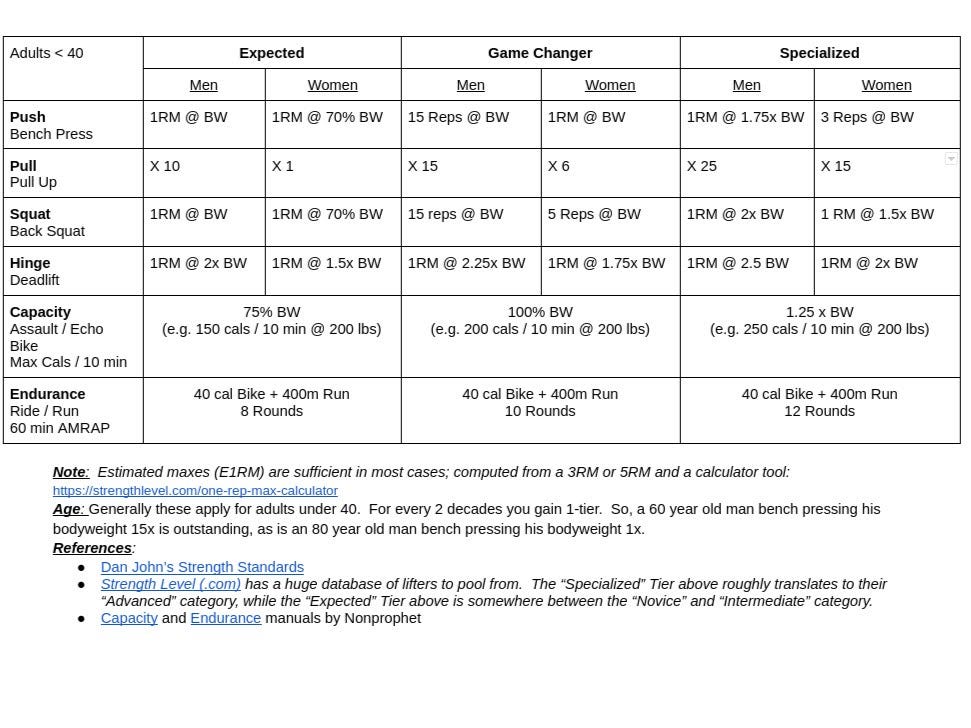

Consider the below benchmarks. If you’re an adult below 41 years old, these should give you an indication of where you’re at (the references have been well sourced elsewhere (ref., ref.). If you’re older than 40, you get a bonus of one category for every 20 years. What is “expected” for a 39 year old is likely a “game changer” for a 55 year old, and exceptional for a 68 year old.

For testing purposes, it isn’t necessary to achieve all the identified metrics within the same week, or even the same month. However, relevancy matters and if it’s been more than 1 year since your last test (of that metric) you’re due for an update / reassessment of your ability.

Strength and Conditioning Benchmarks 2023 (link)

Who is this program for?

Adult (18-40) athletes who cannot yet meet the “Expected” criteria above.

Youth athletes or elderly athletes wanting to build resilience and maintain fitness.

Athletes recovering from injury who want to maintain fitness and mobility during rehab.

Athletes who are in high intensity sports and are looking for mild supplemental fitness.

Understanding benchmarks and end points:

The "goal" of this program will depend greatly on who is using it. The "expected" tier above translates to a novice level of fitness where fitness is the limiting factor in one's ability to practice sport.

The "game changer" tier may be thought of as "most bang for your buck" compared to the "minimum effective dose" of the expected tier. This allows a great deal of latitude of an athlete has a varied number of interests (multiple adjacent sports).

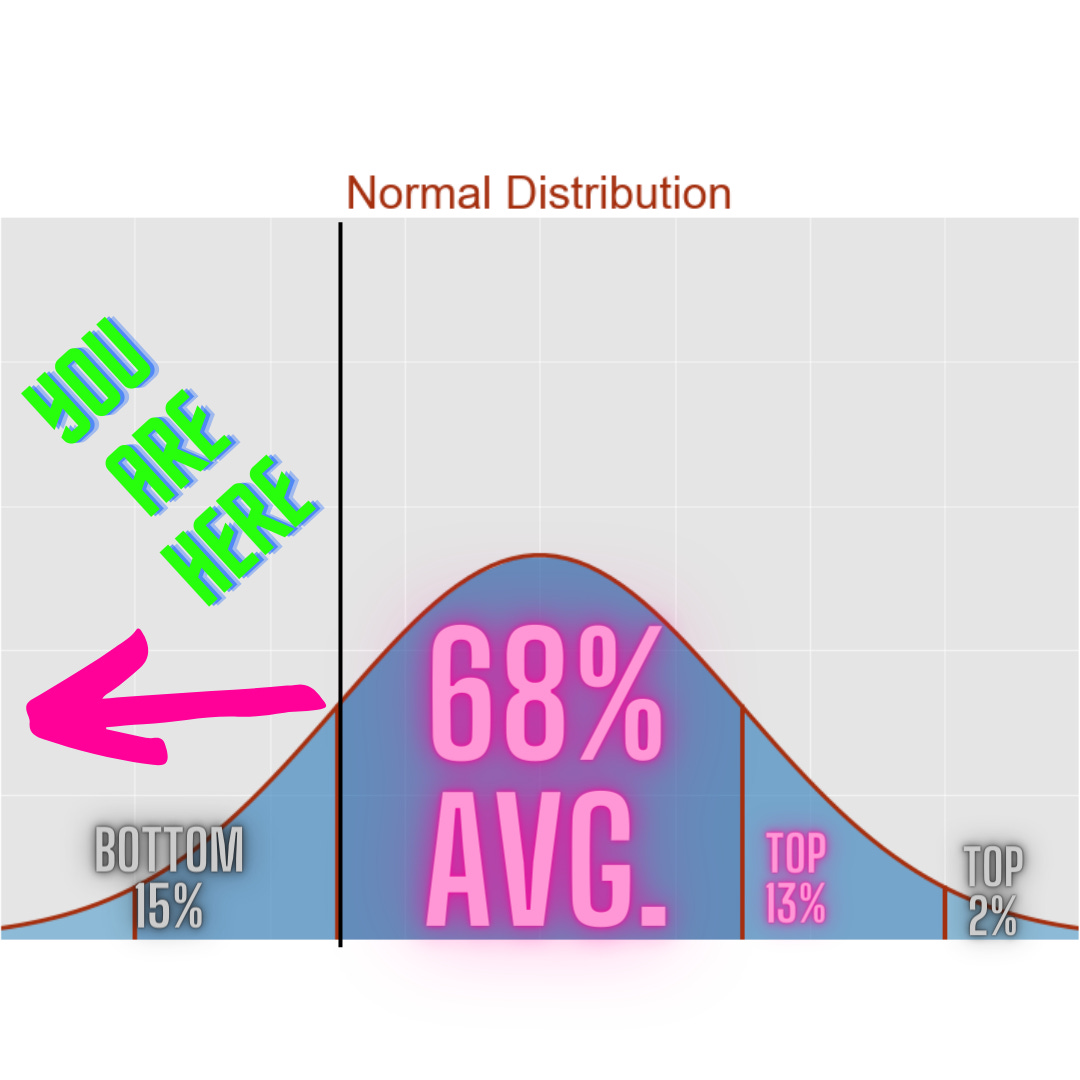

By contrast, the older athlete (age 60+) may have no interest in pursuing fitness beyond daily life functions, in which case the "expected" tier is sufficient. The bell curves (below) then skips a category for age, as do the benchmarks above (what's expected or "average" / middle 68% at age 29 is excellent and in the top 15% at age 62).

Another reason for this approach is that one’s “training age” may be a novice in a given movement category regardless of chronological age. Another possibility is that one’s biological “age” may be subject to injury (“wear and tear” throughout the course of the chronological age). As a result, a more modest intensity may be required to “maintain” a given level of proficiency with a certain movement a longer duration (e.g. the rest of my life versus before next season).

Nevertheless, the "specialized" tier should be possible to achieve without compromising sport practice if one is diligent with recovery and intelligent with their training. There will likely be a need to focus training "blocks" throughout the year (periodization or macro-cycles) as the benchmarks above indicate an "advanced" athlete. Pursuing a given attribute movement further would require significant specialization in that area and likely produce diminishing returns in the realm of sport.

The metrics outlined above in the “Expected” category roughly translate to -1 Standard Deviation (SD) on a normal distribution (“Bell Curve” for the statistics nerds!). For the layman this means that for one reason or another (age, injury, inexperience, etc.) you’re performing in the bottom 15% of all athletes regarding overall fitness.

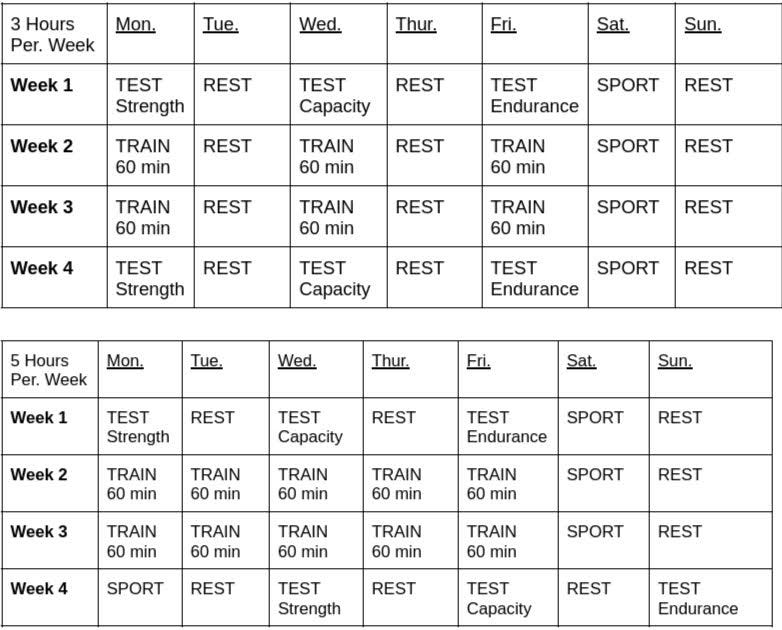

I have set these standards high (relative to the general population) because excellence should be expected. While lofty in some cases, they are not unreasonable. My expectation for athletes is that you already perform above the general population. The American Heart Association recommends a mild 150 minutes of movement per week and 79% of Americans aren’t even getting there (ref., ref.). For the purposes of this program, aiming for 30-60 minutes of exercise movement per day (not including work and house duties) is reasonable. This amounts to 3-5 hours of fitness training per week and a total training volume (including sport practice) of 5-8 hours / week.

Getting started:

The focus of this program is illustrated in the below graphic. In order to get us into a level of fitness that falls within +/- 1 SD of “average” or meeting our assigned benchmarks (“Expected Tier”); we need to focus on General Physical Preparedness (GPP). The term “conditioning” is often not helpful because essentially all training is conditioning our body to respond to a given stimulus – be that a single contraction (strength) or prolonged duration (endurance).

We also want to build a robust enough foundation that we can tolerate increased volume of sport-specific training. For example, the more “generally physically prepared” I am, the more time I can spend training whatever skill or sport I’d like to develop a high level of skill in. In some cases that may just mean squatting and picking up one’s great/grandchildren and walking up/down stairs no matter how old they get. For others it may be the ability to recover from 5 training sessions / week instead of 3.

I’ve long been a fan of minimalist training programs for many reasons. They do, however, have limitations. If we tell ourselves that 5 minutes of mobility work each day is manageable and an acceptable “minimum effective dose”, then there cannot be any exceptions and we cannot miss even a single day!

The trade off is that we cannot error in the opposite direction either and expect to recover in a timely manner from 5 hours of physical training in a single day; particularly if we are in the bottom 15% of a skill / movement area. Your workouts and training program are only as useful as your ability to recover from them.

With that said, we need structure. What we want to avoid is rigidity. Some of the people reading this program are raising a house full of children who invariably get sick, injured, need help with homework, meals cooked, or tucked into bed. So, “life happens” and we need to be able to adapt.

This is why I think it’s helpful to look a bit beyond a daily schedule and consider the totality of a week (month, year, lifetime). It doesn’t matter how hard I kill it this week or this month if I give up and quit next week / month. So, consider a weekly goal for training volume.

This will also give you a measuring stick for what kind of volume you can recover from and adjust your training accordingly.

Total Training Volume: 100%

Fitness Training: 60% - 70% of total volume

Performance / Testing: 10% - 20% of total volume

Sport / Skill Practice: 10% - 20% of total volume

Consider your end point. If the interval between here and there is the next / last 30 years of your life you might scale things differently than if you’re trying to “slim down for summer”, or some other special event or competition. Regardless, the above training volume splits are appropriate for persons in this skill category (below Tier 1) because we are trying to physically prepare ourselves to tolerate more skill practice, and need testing measures (separate from training) to do so.

The program template:

Schedule / Programming: There’s a huge difference between what you can accomplish in 30 minutes / day versus 60. The 3-hour template could be scheduled as 3 x 1-hour sessions or, with a little creativity, 6 x 30-minute sessions. Doubling those time commitments allows both more specificity and varied applications to be developed. Again, we need to see beyond daily volumes and consider what we can sustain for as long as is needed until our goal is achieved. In general, you may have 3-5 sessions per week at:

Warm Up (mobility and resilience): 5-10 min.

Primary Focus (strength): 15-30 min.

Support or Secondary Focus (endurance / GPP): 10-30 min.

Deep Squat: Ideally you want your back to stay flat-ish and your chest projected so that your spine isn’t rounded forward. Also, you ideally want your heels to stay on the ground while your knees point between your big toe and second toe (without caving inwards and pointing towards each other).

Dead Hang: If you cannot hang from a pull up bar (or sit in a deep squat) for 30 seconds, then do it for as long as you can until the sets add up to 30 seconds (e.g. 3 sets of 10 seconds). Before graduating to pull up you could implement a progression of lat pulldown exercises, negative chin ups, chin ups, and negative pull ups.

Animal Crawls: Don’t over complicate this. Act like an unattended 5 year old. A simple YouTube search of “animal crawls” and “safety fall” (or BJJ solo drills) will get you everything from primary school PE class to elite parkour.

Step Counts: There are a myriad of apps and fitness watches that can track this. Making sure we’re adding more (general) movement to our day does improve work capacity and builds towards longer endurance endeavors (though the respective heart rate zone / intensity will vary).

Loaded Carries: Pick any implementation you’d like (Hex bar, Farmer handles, sandbag, partner / pet slung over your shoulder, etc.). Aim for carrying your bodyweight for 100 yards. If you can’t do that, try to chunk it down into sets (e.g. 10 carries for 10 yards each). If you can’t do that, lighten the load and work up to it.

Kettlebell Swings & Bodyweight Movements: Here we’re focusing on a push, pull, hinge, and squat movement that we ideally develop equally, or can focus more on if we’re deficient in that area (see the benchmarks at the beginning of this program). If you’re struggling to wrangle a couple pull ups, then there’s a good chance that just moving your body through unfamiliar patterns (see the animal crawls / rolls section) will be of great benefit.

“Death By…” Format: Keeping equipment minimal is helpful for most people, and at the level this program is intended for, again, moving your body in general will be helpful. The “Death By” structure looks like (for example): doing 1 squat and 1 push up within the first minute, then 2 push ups and 2 squats in the second minute, and proceeding until you cannot complete the prescribed reps in the allotted time. If you cannot do one pull up or push up, you can substitute movement reps for seconds of static hold (e.g. hang from pull up bar for 1 second, 2 seconds, etc.).

10,000 steps or 30/30/30: Many fitness apps and trackers / watches compute “zone minutes.” This isn’t worthless data, but it's more complicated than necessary for this program. There are about 2,000 steps / mile which takes most people 15-20 minutes to walk. So, you could go for 2 miles in the morning, or 10 minutes after each of three meals and you’re halfway there. Additionally, you could consider doing any movement (jogging, jump rope, rowing, biking) for 30 seconds, resting / walking for 30 seconds, and completing 30 rounds (for 15 minutes total).

How long will this take?

The trite answer is, “as long as it needs.” Remember, we aren’t specializing training with this program, we are generalizing. So, theoretically you could go on doing the things in this program for the rest of your life.

When is it time to move on / make things more complicated? The answer is: when you are absolutely certain of your foundation and when your goals and ability necessitate it.

This program is intended to be quite broad. Who is reading it? A 13 year old Division I college prospect? A competitive recreational athlete coming off an injury? A senior citizen? The templates provided above are given as guidelines rather than prescriptions. Start conservatively. When something feels “easy” then you can “make it harder.” However, resist the urge to “make it complicated” until you’re absolutely sure:

What you say you’re doing is what you’re actually doing.

What you’re doing isn’t working, and

You know why it isn’t working, and

You have a reason and rationale for introducing said difficulty / complications, then

Test the effectiveness of the added complication (as its own intervention).

Testing: With that said, testing for the novice athlete can occur more frequently, as often as every 2 - 4 weeks, because they will see stimulus adaptations much more quickly than more advanced athletes. While testing should be incorporated into training, as it counts towards total volume, a given test should not be used as training itself (e.g. simply doing the test every day).

The above are samples only. Accurate testing should reveal strengths and weaknesses. This program can easily be stacked on top of sport training if one is experienced at their sport, but lacking in terms of fitness. Therefore, testing should reveal where one is weak, and thereby where they should focus their training.

Again, there is a huge deviation between the adolescent or senior citizen training 3 hours per week, and competitive amateur athletes attempting to round out their fitness after a layoff. The results of a given test require intelligent application to be useful. Do so judiciously with both your starting and endpoints in mind.

Sleep and nutrition:

Everybody needs to sleep and eat. Accordingly, those are two of the biggest factors that contribute to one’s ability to recover. It’s worth saying again that one’s ability to perform is directly dependent on their ability to recover. This is not primarily a nutrition program, so these recommendations are very general and allow for a lot of latitude within various “whole foods / ancestral health” modalities (e.g. Paleo, Keto, Carnivore, Whole 30, etc.).

Sleep: One’s exact sleep need is difficult to calculate, and the neurosis that can accompany apps / devices combined with their inaccuracies can often be less than helpful. In general, consider 7-9 hours of total sleep time, but what’s more is the quality of your sleep. Do you feel rested when you wake up? How dependent are you on stimulants? In general, consider the following (ref., ref., ref.):

Avoid caffeine 6-12 hours before bed (half-lives and sensitivities vary).

Avoid blue light / screens 1-2 hours before bed.

Keep your bedroom cool and blacked out.

Get sunlight in your eyes as soon as you can upon waking.

Protein: A common recommendation is for 1 gram (g) of protein per pound (lb) of bodyweight, or 2g / kilogram (Kg) of bodyweight. There’s some variance in recommendations here regarding total bodyweight versus goal bodyweight, and 2-3g / Kg. If you’re getting anywhere close to that and prioritizing animal sources, you’re getting an incredible amount of nutrients. For the purposes of this program, I’m not concerned with whatever else you eat if you still have the appetite for it after packing in 3g of animal protein / Kg of bodyweight. Animal sources of protein are far superior in terms of bioavailability and nutrient density compared to plant proteins (ref.).

Additional general recommendations would include:

Avoid vegetable / seed oils (canola, palm, soy, cottonseed, corn, etc.)

Avoid all grains (rice, bread, pasts, legumes, beans, etc.)

Avoid the sugary processed junk you already know is bad (cookies, candy, etc.)

Prioritize whole foods and do not worry about counting calories, carbs, etc. for now. The graphic below is for general purposes only. Some people may need a lot more fuel (calories) than this, it’s just demonstrating that there’s quite a bit there already if we’re sourcing appropriately from animal protein.

Hydration / Salt: Contrary to the American Heart Association’s accusations against salt, JAMA’s own findings indicate that the sodium intake with the lowest rate of all cause mortality is 4-6 grams; however lifestyle factors contribute to a higher need as well (ref., ref., ref.). For reference, there is about 2g of sodium (Na) per teaspoon (tsp) of salt (NaCl). A sample starting point may look like this:

1 Cup bone broth at morning and night (0.5g - 1g of sodium each).

1/2 tsp salt in 1 liter (L) of water anytime before your workout.

1/2 tsp salt in 1L of water during your workout.

1/2 tsp salt in 1L of water anytime after your workout

I have an affiliation with Redmond Real Salt / Re-Lyte ancient salt and electrolyte supplements (15% off code: savagezen)

For the purposes of this training plan we don’t need an intensive course in biology or neuro-musculature. We need to know what is going to be most effective so that simplicity can be our ally in developing consistency and longevity. Remember, the best plan in the world doesn’t mean anything if you don’t actually do it – or give up / quit in two weeks.

There is truth to the expression that you can’t outwork a shitty diet. It will eventually catch up to you, if not in direct terms of performance, then indirectly by affecting longevity – which you will need if you want to get or be good at anything. You’ll need to survive being bad at it first.

It is also true that there are numerous examples of not just professional athletes, but the first class of world class athletes, with notoriously terrible diets (BigMacs, fries, nachos, etc.). It is debatable whether their performance is because of or in spite of their diet. At any rate, this program isn’t inherently about nutrition or weight loss. If you need to lose a few pounds to feel, look, or perform better; you probably didn’t need me to tell you that.

If you’re so inclined to pursue a specific meal plan or want to delve into nutritional practices further see the Additional References at the end of this document for a recommended reading list amenable to this program.

Goal: Get after it!

Hope is not a plan and planning isn’t action. So, do, and learn. Go forth.

Additional Resources:

Tools:

Strength standards on strengthlevel.com

Training Books:

Strength Standards by Dan John

Now What by Dan John

Capacity Manual by Nonprophet

Endurance Manual by Nonprophet

Nutrition Books:

Sacred Cow by Diana Rodgers and Robb Wolf

Wired to Eat by Robb Wolf

Why We Get Sick by Benjamin Bikman