The influence of breathing on the central nervous system

Bordoni: Cureus: diphragm, breathing, phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, neural oscillation

Many of you know that I’m very fond of the work of Shift Adapt and the Human Health and Performance Foundation. Breath is a fascinating seguay between things we can and cannot control, and also allows us to participate more intentionally with our physilogy — rather than at the mercy of it.

This article, and several mentioned below, illustrate how breath changes blood flow to our brain, accuracy of memory recall, and emotional recognition.

To start us off, “the diphragmn is the motor muscle of breath, which can be automatic, forced, or controlled.” I’ve mentioned in other posts that forced breathing can be damaging. Automatic breathing is what we do most of the time, but pathological emotional, behavioral, somatic, or cognitive factors take over our lives if we do not make an intentional practice of our breathing — at least intermittently.

The phrenic nerve sends motor information to the diaphragmn and connects the sympathetic nervous system to the adrenal gland. The vagus nerve serves a similar function, but lower down the spine, from ther cervical to abdominal levels.

The referenced paper here notes several intersting changes in our physiology based on our breathing. At the top level, inhiliation moves blood to the brain while exhalation moves blood away from it.

“It has been demonstrated on a human model that a variation of cerebral blood flow is able to produce action potentials, which can be recorded with EEG… Blood pressure changes may directly stimulate an electrical response of brain neurones, with small variations in microvolts.”

This means that our breathing can regulate our blood pressure, which in turn changes both the blood flow to our brain and the voltage the brain procduces.

“"Breath has patterns. Schemes create behavior. Breath is a behavior. Behavior represents the person. Breath reveals the person.”

Bordoni, B., Purgol, S., Bizzarri, A., Modica, M., & Bruno, M. (2018). The influence of breathing on the central nervous system. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2724

A colleague and I were discussing traumatic brain injuries (TBI), both chronic and acute and he asked me if I was familiar with any literature on the subject. Immediately I thought of breath work (and ketosis) as powerful interventions, but wasn’t familiar with any literature off hand.

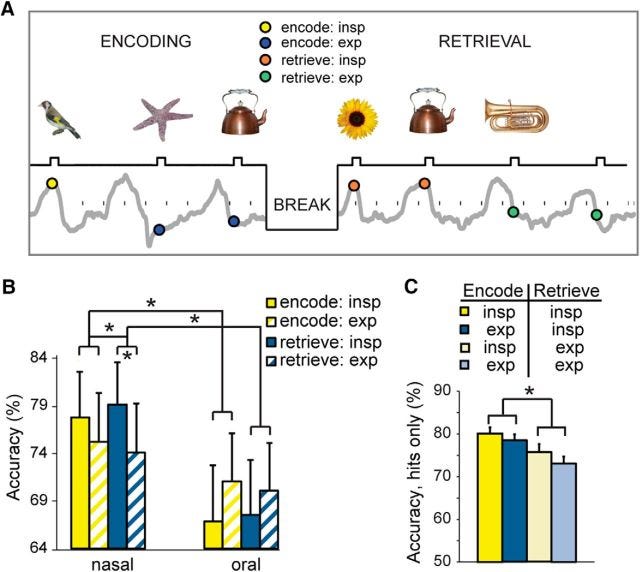

A 2016 study (ref.) showed that recognition of facial emotions (specifically fear, but not surprise) were detected more quickly during nasal inspirations (inhaling) than during expiration (exhaling). People were also generally faster at recognizing emotions on presented facial pictures faster while breathing nasally.

This feature isn’t exactly specific to TBI, but it’s very relevant to the overal functioning of emotional regulation (DBT) and mentalization of the self and other (MBT).

Regarding memory, the same study noted that “… retrieval accuracy was higher for those picture items that had been encoded during the inspiratory phase of breathing, and was also higher for the picture items retrieved during inspiration, for the nasal route only.”

If we consider the contents of the first study I referenced, this makes a lot of sense. When we inhale, we’re stimulating our nervous system, getting more blood to our brain, and while we do retain / learn information better, our emotional sensitivity is more attuned to fear than surprise.

This is a key component for understanding how humans learn; specifically an “optimal level of difficulty.” We need enough resistance to push against until we can push ourselves — something corrective. However, too much resistance makes us accostomed to, and perhaps expectant of, failure — we get crushed into hypo- or hyper-activation — the proverbial fight, flight, freeze, or feint reflex.

Importantly, the second study here notes “Our findings imply that, rather than being a passive target of heightened arousal or vigilance, the phase of natural breathing is actively used to promote oscillatory synchrony and to optimize information processing in brain areas mediating goal-directed behaviors.”

In other words, arousal (sexually, emotionally, intellectually) is beneficial for learning and distinguishable from both hyper- and hypo-arousal.

Interventionally then, slow breathing was defined in one journal (ref.) as 4 - 10 breaths / minute. In general, down-regulatory factors involve:

reducing respiration rate (breaths / min)

breathing through our nose (versus mouth)

extending expiration (longer exhales than inhales)

Typically, down regulation is what most people are in need of, whether you’re a geeked up go-getter (“type a” personality) or watching too much “news” and glued to blue-light devices (anything with a screen).

Hopever, it should also be noted that traumatic (psychological or somatic) brain injuries can also elicit a hypo-activation reponse; proverbeal “lid flipping” down rather than up.

In that case, Wim Hof’s breath protocol may be useful because it is a hyperventilation protocol which would tend to up-regulate and stimulate the nervous system and blood flow.

From a clinical perspective it’s important to not confuse these protocol and their respective applications because they can have iatrogenic effects that are just as powerful as what we’re hoping to resolve.