Duration Builds, Intensity Sharpens

Are you addicted to high-intensity? Maybe the opposite, you always want things to feel like a comfortable slog. The truth is that too much intensity makes things brittle, and too much duration makes them dull.

For many years I told myself that “the best use of mat time is your training partners.” What I mean is that sport-specific, technical development, can only be done in the “field of play.”

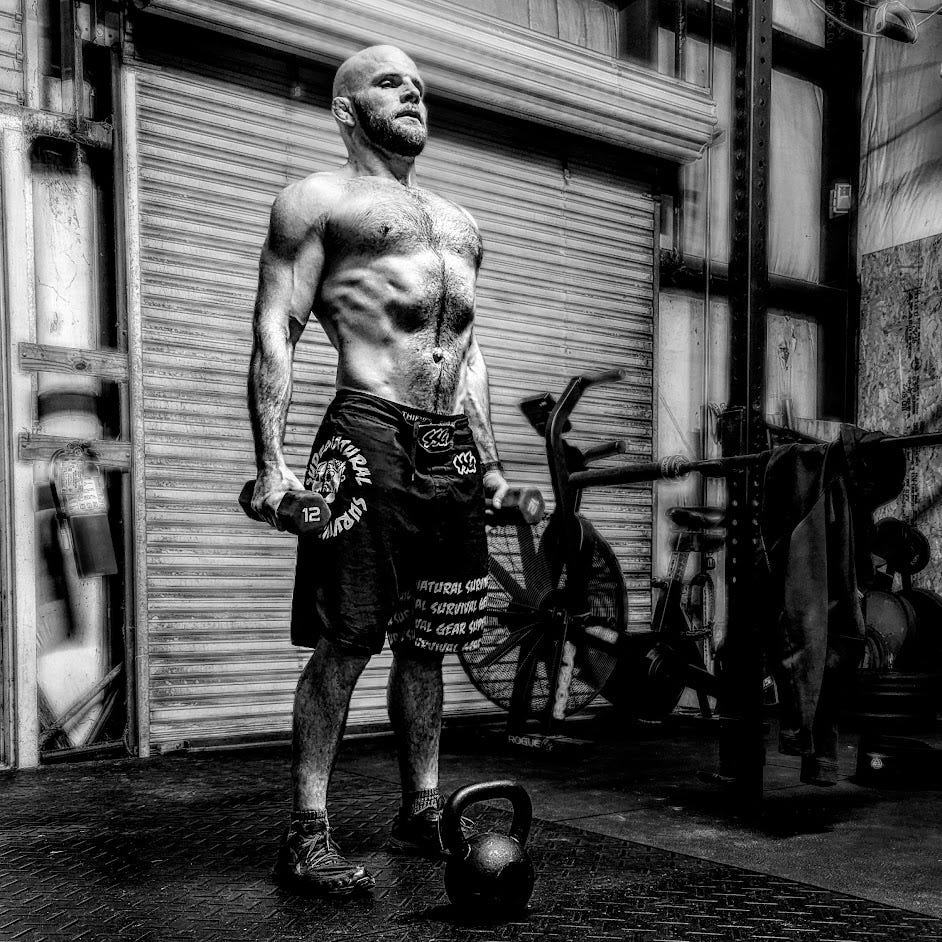

By contrast, you can always “push the throttle harder” to develop your fitness and physical assets off-the-mat or off-the-field.

“Conditioning” means converting “gym strength” (or another fitness attribute) into something functional. By functional I don’t mean whatever “weaponized specificity” charlatans are hocking on social media. I mean real delivered in-game results — e.g. passing yards, free throws, takedowns, fewer injuries, etc.

Synthetic environments like the weight room allow us to isolate, measure, and develop specific attributes much better than the dynamic wilds of sparring / scrimmage, let alone competition.

I still stand by my original premise, that doing the thing you want to get good at is the best way to do so. However, it may be much more of a question of quality rather than quantity or intensity. This may be especially true if the intensity doesn’t have a specified intent or duration limit, or if years of training volume have already been accumulated.

That brings us to John Danaher’s knife metaphor. John notoriously gives his students knives when he promotes them. The rationale he’s provided is that training is like forging a knife, it’s a cycle between hardening and sharpening.

The “harder” the metal, or broader the athlete’s skill set, the more difficult it will be to sharpen. It gets dull. By contrast, always sharpening makes things brittle (prone to injury, etc.); by definition one cannot hold their “peak” indefinitely lest it becomes a plateau.

Grappling (or martial arts in general) doesn’t have a “season” like traditional team / ball sports. That muddies the water somewhat because we miss the natural cycle of “hardening” or broadening our skills in the off-seasons and “sharpening” them (at the exclusion of developing others) in the in-season or “fight camp.”

“Sport taught me that duration builds, intensity sharpens…”

~ NonProphet Endurance Manual (p53)

A modest amount of insight will reveal what you value, and where you’re lacking. Endurance folks value volume. Strength and power folks value load. Nutritionists will tell you food fixes everything. Conditioning coaches will prioritize the force over the fulcrum, and technicians the reverse.

Clearly we need both hardness and sharpness. As mentioned above, which one to prioritize may be dictated by a competitive season or cycle. For others it may come down to their “training age” and development. “General Physical Preparedness” (GPP) is a real thing, and tends to be lacking at both ends of the training career.

“There’s no point in honing unhardened teeth…”

~ NonProphet Endurance Manual (p53)

To piggy back off of Danaher, you don’t try to sharpen soft steel. So, the hardening must come first in the forging process.

Glass cannons and flashes in the pan never last. Regardless of how spectacular their performances or promising their potential, they are living proof that high-heat is unsustainable. There are lots of metaphors for this, cooking, erosion, or the number of 40+ year old medalists at the last ADCC.

How much “hardening” do we need to do? If you’re young, old, obese, or get winded tying your shoes, prioritizing physical limitations is probably going to pay great dividends towards keeping you on the mat and doing more of the thing(s) you love.

The purpose or intent of hardening doesn’t change much after that. However, the dosage and direction probably does. As injuries pop up, acute or from chronic overuse / neglect, those un-hard spots will become evident and need to be addressed. Hopefully, we can do this proactively.

“Intensity gets me high. It doesn’t take much. And it’s easy to mistake the high for the objective…”

~ NonProphet Endurance Manual (p53)

“Regression towards the mean” is a statistical term to describe the phenomenon that as a sample size grows, there is a decreasingly small number of outliers from the average.

In training terms, this means that the more we try to “go hard” (like setting a PR), the more dull and the more “average” our performances become. The delusion is that the sessions still “feel” hard despite lackluster output.

You have to ask yourself, and answer honestly, do I want to “feel” like I’m training hard, or do I want to produce spectacular results? The caveat here is that the later cannot be purchased on credit. You need the currency of recovery already in the bank.

Only in recent months have I “put my money where my mouth is” in terms of how I spend my training time; or more accurately, what I spend my time recovering from. Not all energy systems tax the body proportionately; certainly not depending on one’s level and style of previous training and adaptation.

In terms of grappling, my problem isn’t time. I’ve put in the time. It’s effort, but not in the way you might think. I can still roll and fight hard, but just how hard is going to be directly proportionate to how often I want to go all in.

Learning to moderate volume and intensity is valuable skill that becomes all the more necessary as you age.

The part I got wrong in my original thesis was that in practice I let “hard grappling” replace “sharp grappling.” Earlier in this essay you may have thought that’s where I was leaning, that one should do “harder” rounds instead of “more” (volume of) rounds.

Quality counts. Intentionality and focus count.

The first mistake I made was prioritizing performance over recovery — call it feeling good or “longevity” if you’d like. The second mistake was misplacing effort (of both performance and recovery) on nutrition, and then fitness, in hopes it would magically translate 1:1 for grappling. The third mistake was resorting to (grappling) volume without considering quality of movements and skill progression (i.e. sharpening rather than repeating what I already knew).

That has all taken place in the 18 months or so since I earned my black belt. Cheers to the next 18 months before I get a stripe on that belt, and of course to the new year!

“Good rest is better than bad practice”

~ Chris Wojcik