Lessons from Climbers and the Arndt-Schultz Law

Ah, the allure of minimalism and (bio/life)hacking. I’m as guilty as anyone of wanting to distill the world down to “shark habits.” The trouble is, the same kind of vigor and tenacity tends towards “missing the forest for the trees” or “majoring in the minors;” a “horseshoe effect” of health and fitness if you will.

A recent blog post from Steve at ClimbStrong got me thinking about how minimalism often betrays us and belies our attempts to continue to avoid the hard work we know will be… well, hard (and uncomfortable… and the segue to change).

The Arndt-Schultz Theory:

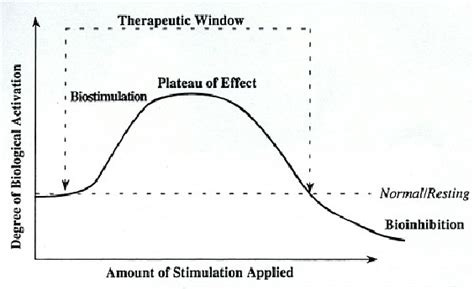

The Arndt-Schultz theory states that “stimuli that fall short of the threshold have no training effect.” In other words, a training stimuli (e.g. running. lifting, etc.) needs to have a certain intensity, a disruption of homeostasis, in order to provoke adaptation (i.e. improvement).

Steve write (in climbing terms):

“Too many easy pitches, light sets, and volume days can potentially result in no progress, which can be really hard on the motivation, especially when we think we’re “rebuilding.” This is doubly confusing when we hear about No Hang training, bodyweight-only strength routines, and great climbers who seem to just go do tons of pitches.

The key here is to push your system to the edge of what it can handle. A 5.12 climber doing volume on 5.9 will have to do a lot of volume to get a stimulus. When loading up exercises, we need to find a place where each one takes us close to, but not over the limit.”

Those numbers don’t have to mean anything to you, just recall the that lifecycle of any effort closely mirrors the “stages of grief.”

Hope - confidence.

Denial - how can this be so hard?

Despair - the black zone, you’re too far in to turn back now.

Acceptance - you’re going to make it.

That Stage 3 (despair) is arguably the worst. It’s what most people - certainly including myself - try desperately to cognitively, emotionally, and otherwise find top-down justifications for avoiding. As my man Brain Mackenzie put it:

“The only truth is that when we become healthy, we change.”

In other words “noob gains” are confidence builders. They feel fun, and are sometimes useful. They can definitely break up the monotony that precedes despair. However, no amount of “functional” resistance bands or kettlebells are ever going to supplant the barbell in terms of maximal loading.

Similarly, as I’ve discussed many times before, going “harder” in a direction you’re already comfortable with isn’t capable of addressing your weakness any more than the folly above.

Minimalism isn’t inherently efficient, it can leave us subject to an infinite regression. That is, we take such small bites, that the reality of achieving our goal is reduced to an impossibility.

The Forgotten Art of (Long) Warm Ups:

If you recall some of my training notes from the Escape Velocity Program (ref., ref - review link), then you know that while an intense effort is counter intuitive to “motor learning”, it is essential for physiological adaptation. An important note here is whether we’re discussing physicality or skill acquisition.

Steve reminds us:

“A good warm-up will take a lot of your training session. You might be tempted to spend more time training and less time warming up. This would be wrong.

If you don’t have time for the warm-up, a serious look at your minute-by-minute schedule in a day is warranted.”

A proper warm up should adequately “pre-fatigue” and prepare us for the primary “working” task. A small caveat is that we want to prepare, but not pre-fatigue before a “test.” However, a true test should be a thing of rarity.

Anaerobic Lactic / Glycolytic Metabolism:

“…is far from the predominant energy system in climbing”, but what about MMA / boxing / grappling?

I’ve cited this many times (ref.), but striking sports are more aerobic, and the more grappling-ish a discipline becomes, the more strength oriented it becomes; however the foundation of aerobic fitness is undeniable in any case. The “oxidative” energy system contribution is always 50% (or more) in every round of karate, taekwondo, judo, and boxing.

Combat sports, particularly of the grappling variety, are what’s referred to as “repeat sprint sports.” That essentially means we have intervals within an interval — a flurry of strikes, a takedown attempt, scramble back to the feet, pacing and sizing each other up, and repeat.

This is one of the hallmarks of capacity training, recoverability. But, that’s not just between rounds, it’s between interval efforts of explosiveness or scrambles within the round as well.

We’re then left with two possible training lineages:

Endurance > O2 Mobilization > Recoverability

Mobility > Power > Strength > Recoverability

I can tell you right away which option I want to train more, and suspect most grapplers would agree with me — it’s No. 2.

But this is where the wheels sort of fall of and specificity belies the truth. By always training HIIT, or MetCon, or whatever you want to call it — I choose “recoverability” — you actually miss the point. You believe that because it is “functional”, because it is “sport-specific”, that other faculties are inferior.

Here’s the problem. The specificities of your deficits override sport-specific generalities. By always training to be “good” in the middle, you never succeed at either extreme — power or endurance.

While it is true that you cannot “endure” your way through a true 1 or 3-rep max, you also cannot “strength” your way through a 10-minute AirBike test (e.g. for max calories, O2 Mobilization).

Even in the first minute of Olympic judo — the most explosive of 5 minutes with 40% of energy expenditure coming from the ATP system — 50% of energy expenditure comes from the aerobic system. That’s a bitter pill to swallow for “a strength guy” like myself.

Practical Application:

Does this mean 50% of grapplers’ training should be aerobic? Probably not, but maybe for a time. I still mostly stand by my old hypothesis of Barbells and Bell Curves that for 70% of athletes, spending 70% of their time doing the thing they want to get good at (e.g. sport practice) is the right recipe.

The 15% worst athletes will needs accommodations (likely for fitness) and the 15% best athletes will need specificity either for novel stimulation to provoke further adaptation, or to address overuse injuries.

Put another way, unless you’re in the 15% best of your sport, you probably don’t need to artificially mimic a sport’s exact energy system outside the mat / ring / field / court with supplemental training because you’re already getting a lot of that “in-game.”

In other words, don’t waste time with what you’re already good at — the inverse of our Arndt-Schultz Theory. On the other hand we can’t take such little bites at our deficient systems and functions that no appreciable change ever occurs.

I was talking to a white belt recently, and in my classes we have been wrestling heavy, and he developed some tennis elbow. He took a few days off, then showed up at open mat to wrestle hard again. He’s a strong guy. He’d been lifting on the “off days.” He wondered why his elbow was hurt again.

You can rest an injury all you want, and if you keep doing what you did before, you can expect the same injury to repeat. I told him he needed to decide what’s important and make that the focus of his training; he’s just going to repeat the injury cycle if he doesn’t learn to train differently.

Let’s assume there are enough grapplers in the world that skill levels do in fact fall on a standard distribution, a “bell curve.” 70% of grapplers are going to be +/- 1 standard deviation of “average” skill — blue to brown belt.

If 70% of your training time is spent training grappling (and thereby on “recoverability” via sparring), then you’ve got 30% to work with. A 5-minute mobility routine pre or post grappling training may be sufficient if you already have decent mobility and are looking to “grease the groove” a little bit. But that’s not going to cut it if it’s a serious limiting factor.

The same goes for “cardio”, endurance work, real LISS and long endurance work. Spending 50% of your supplemental training time addressing a specific deficit in your physicality sounds like a dang good idea.

The other 50% of supplemental training time might be spent “maintaining” things you’re already good at — which will likely help overall moral since if you’re good at something you likely enjoy it. However, some of that remaining 50% will also need to be allotted to movements and systems “in support of” the primary objective (the limitation you’re addressing)

Example 1: Average Player

Weekly Training Time: 10 hours

Sport Focus (70%): 7 hours (BJJ / recoverability)

Support (30%): 3 hours (Fitness)

Limitation (15% of total): 1.5 hours (endurance)

Support (7.5% of total): 45 min (mobility / O2 mobilization)

Morale (7.5% of total): 45 min (strength / power / recoverability)

Example 2: Average Player

Weekly Training Time: 5 hours

Sport Focus (70%): 3.5 hours (BJJ / recoverability)

Support (30%): 1.5 hours (Fitness)

Limitation (15% of total): 45 min (endurance)

Support (7.5% of total): 20 min (mobility / O2 mobilization)

Morale (7.5% of total): 20 min (strength / power / recoverability)

Example 3: Out-of-Shape White Belt

Weekly Training Time: 5 hours

Sport Focus (30%): 2 hours (BJJ)

Support (70%, assuming this is the limiting factor): 3.5 hours (Fitness)

Limitation: 45 min (recoverability)

Support: 20 min (endurance)

Morale: 20 min (strength / mobility)